William Shakespeare, the Bard of Avon (1564-1616)

Just as the digital revolution of the late 20th century has transformed the world around you while adding new words and concepts to your vocabulary, as the 16th century England saw a similar burst of creativity and ripples of transformation, and this is the very time frame that shaped and was shaped by William Shakespeare.

Before we commence our discussion on Hamlet, let’s envision the young Shakespeare witnessing and processing these changes in his poetic vision. He was born into the world of literary symbolism—Queen Elizabeth the First tacitly fostered the cult of the Virgin Queen and all her courtiers vied to “woo” the “fair(y) queen” to secure self-promotion. The printing press Johannes Gutenberg invented in 1439 finally reached the English shore to spawn aspirant writers and translators, who eagerly churned out pamphlets and booklets.

The educated and the elite had favored Latin and French to English, yet now there was a definite sea change and even the future king James the First was to commission the bible to be translated from the languages of the exclusive elite (Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Aramaic) into the English vernacular. Thomas Wyatt had imported the Petrarchan (aka Italian) sonnet and attempted to Anglicize it suitable for the English tongue and decorum. As if to give wing to the English, the fortuitous defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 helped catapult the English to global hegemony (that is, dominance) and now the English dreamed of expanding their insular world to the brave new world (the American colony, the Indian subcontinent, and the small and large islands between the seas).

At this juncture, Shakespeare walks into this bustling scene of creativity, experiment, expansion, and prosperity. Born in a small town called Stratford-upon-Avon (a village called Stratford near the small rivulet called Avon), the young Shakespeare runs away from a shotgun marriage to Anne Hathaway (a seven-year senior to Shakespeare) and joins the theater troupe as a novice actor and soon transforms into a poet and playwright. By 1616, Shakespeare is to own the largest house in Stratford and to become one of the shareholders of the acting company, King’s Men. This man we honor as the Bard.

Shakespeare, the Bard of Avon, shaped the relatively flexible English (its spelling and pronunciation was yet to be standardized) by playing free and easy. For example, he used nouns as verbs as in “it out-herods Herod” and “uncle me no uncle.” Some even contend that he coined an estimated 2,000 neologisms (some illustrious examples include “bare-faced,” “gnarled,” “lackluster,” and “fitful”).

He also invented countless phrases commonly used even today such as “one fell swoop,” “vanish into thin air,” “brave new world,” “star-crossed lovers,” “there’s the rub,” “it's Greek to me,” “cruel only to be kind,” and so on and so forth. And he was more than happy to “borrow” from known sources and other writers (the copyright law was conceived not until 1709—Will, you lucky devil!). He penned 36 plays and 154 sonnets and perfected puns and blank verse (unrhymed units of iambic pentameter).

Whatever the merits of the other poets of this golden age, undoubtedly it is William Shakespeare who single-handedly fashioned the English language and literature for the times to come.

What one fact or observation of the Bard would you like to share with us?

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1596?)

Royal Shakespeare Company Learning Corner:

https://www.rsc.org.uk/shakespeare-learning-zone/a-midsummer-nights-dream

Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark (1600?)

Royal Shakespeare Company Learning Corner:

https://www.rsc.org.uk/shakespeare-learning-zone/hamlet

|

|

|

|

|

|

Based on Act One, Scenes 1, 4, and 5

|

In the following speech, Claudius tries to appease Hamlet by saying that we all share the "common theme" of the "death of fathers." Claudius maintains that excessive mourning is vulgar and unnatural because the death of the beloved is such a commonplace. Truth be told, Claudius attempts to manipulate Hamlet by dispersing his brooding melancholy and will to rebel. |

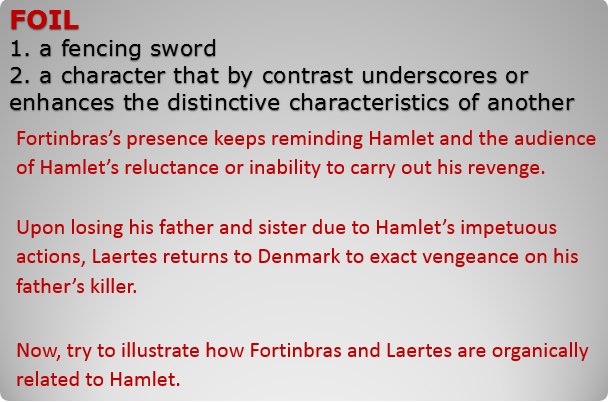

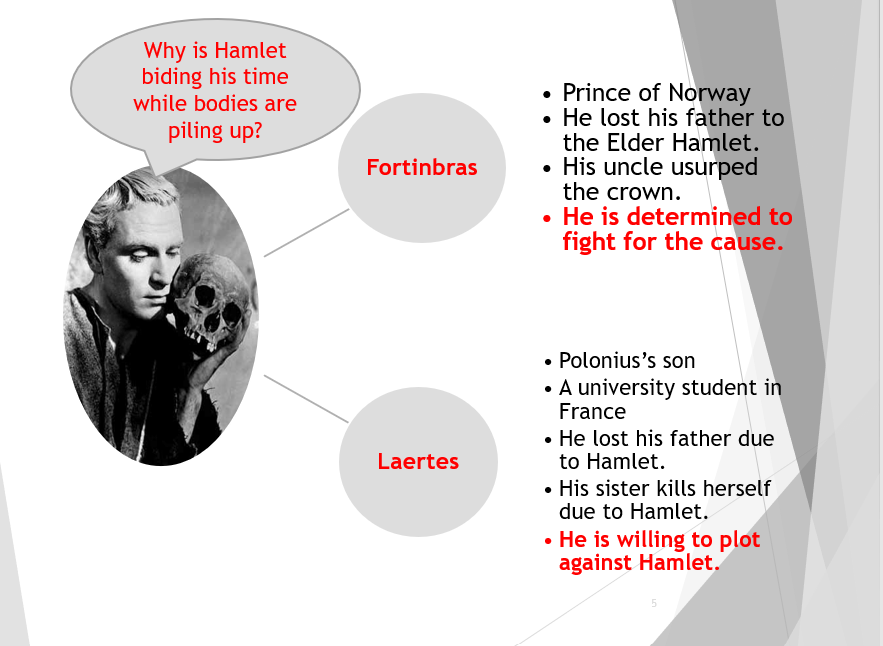

Yet, in spite of himself, Claudius betrays an ironic truth that the underlying theme of this play is the duty of a son who has to honor his slain father. There are three young men and a young woman in similar circumstances who have to contend with the death of their fathers: Hamlet, Fortinbras, Laertes, and Ophelia. These literary foils provide a contrast that helps illustrate Hamlet's struggles and frustration. |

Political Hamlet

|

Royal Exigence: What makes a king a good one?

|

|

|

|

|