An oxymoron is a phrase that seems self-contradictory or incompatible with reality. By juxtaposing two opposite words (that is A + Not A as in "living dead"), writers seek to achieve dramatic contradiction or vivid imagery. | Eloquent silence |

|

1 Comment

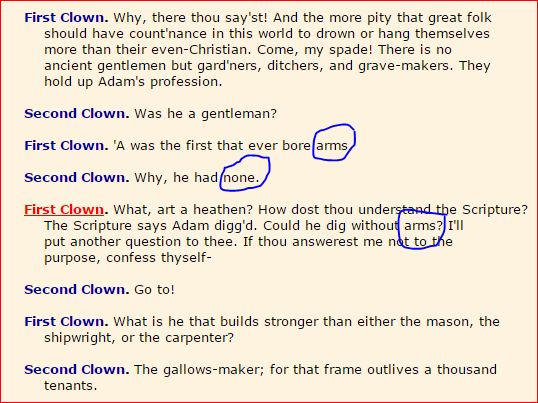

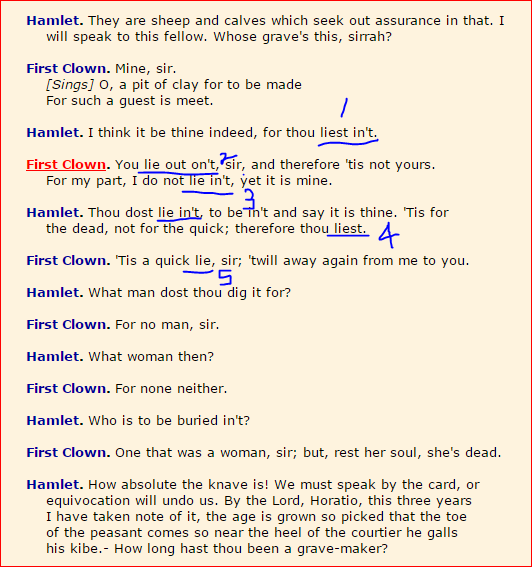

An apostrophe is a figurative device in which the speaker calls out an absent person or an inanimate object or concept in order to express his or her emotion. Hence, you may see the apostrophe is often used alongside an exclamation mark.

Oh wind, caress me with your many nurturing hands. Calling out an inanimate object (the wind) to address it = apostrophe Ascribing human features (hands) to the wind = personification Attributing human emotions (nurturing) to the wind = pathetic fallacy Oh clouds, cover my shame with your forgiving arms. Calling out an inanimate object (clouds) to address them = apostrophe Ascribing human features (arms) to clouds = personification Attributing human emotions (forgiving) to clouds = pathetic fallacy Daisy, what a splendid smile you bounteously bestow on me. Calling out an inanimate object (daisy) to address it = apostrophe Ascribing human features (smile) to a daisy = personification Attributing human emotions (bounteous = generous) to the daisy = pathetic fallacy Rain, you messenger of sad tidings with teary eyes. Calling out an inanimate object (rain) to address it = apostrophe Ascribing human features (eyes, playing a role as a messenger) to rain = personification Attributing human emotions (ability to deliver sad news) to rain = pathetic fallacy Ye chaste stars, stop crying over the night. Calling out inanimate objects (stars) to address them = apostrophe Ascribing human features (tears and eyes) to stars = personification Attributing human emotions (chaste meaning pure, innocent) to stars = pathetic fallacy Parody, as a literary genre, is an imitation of a particular writer, artist or a genre, exaggerating it deliberately to produce a comic effect. Parody imitates or exaggerates a subject directly to produce a comical effect. Satire, on the other hand, makes fun of a subject without a direct imitation. Moreover, satire aims at correcting shortcomings in society by criticizing them. Literary Examples of Parody Example 1: Shakespeare's “Sonnet 130” parodies the Petrarchan conceit. My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips’ red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. Unlike Petrarch's Laura, Shakespeare's "Dark Lady" does not have starry eyes, coral lips, or a snow-white complexion. Poking fun at the Petrarchan clichés, Shakespeare breathed a new life into the English language. Example 2: Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels Synecdoche is a literary device in which a part of something represents the whole. Synecdoche may also use larger groups to refer to smaller groups. It may also call a thing by the name of the material it is made of or it may refer to a thing in a container or packing by the name of that container or packing. Synecdoche is often misidentified as metonymy (another literary device). Both may resemble each other to some extent but they are not the same. Synecdoche refers to the whole of a thing by the name of any one of its parts. For example, calling a car “wheels” is a synecdoche because a part of a car “wheels” stands for the whole car. However, in metonymy, the word we use to describe another thing is closely linked to that particular thing, but is not necessarily a part of it. For example, “crown” that refers to power or authority is a metonymy used to replace the word “king” or “queen.” Examples of Synecdoche: The word “bread” refers to food or money as in “Writing is my bread and butter” or “sole breadwinner.” The phrase “gray beard” refers to an old man. The word “sails” refers to a whole ship. The word “suits” refers to businessmen. The word “boots” usually refers to soldiers. The term “coke” is a common synecdoche for all carbonated drinks. The word “glasses” refers to spectacles. “Coppers” often refers to coins. Literary Examples of Synecdoche: Example 1 Coleridge employs synecdoche in his poem "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner": The western wave was all a-flame. The day was well was nigh done! Almost upon the western wave [ = the ocean] Rested the broad bright Sun. Example 2 Shelly's "Ozymandias": Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand [ = the sculptor] that mocked them. Example 3 Joseph Conrad's "The Secret Sharer": At midnight I went on deck, and to my mate’s great surprise put the ship round on the other tack. His terrible whiskers [ = the whole face of the narrator's mate] flitted round me in silent criticism. Example 4 Jonathan Swift's "The Description of the Morning": Prepar’d to scrub the entry and the stairs. The youth with broomy stumps [ = the whole broom] began to trace. The use of synecdoche helps writers to achieve brevity. For instance, saying “Soldiers were equipped with steel” is more concise than saying “The soldiers were equipped with swords, knives, daggers, arrows etc.” Let's learn the importance of education through the presidential examples of malapropism. Trump uses "unpresidented" in the place of "unprecedented"; "hear by" in lieu of "hereby." What other "presidential" examples of malapropism do you know? he Rivals (1775) by Richard Sheridan Chapter 16 of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn depicts the hypocrisy of the slave-hunters, which provides a hilarious solution to Huck's dilemma: whether to honor the social norm of slavery or to follow his own mischievous, yet kindly heart. In what ways does Mark Twain mock the slave-hunters? Do you think Huck made the right decision by lying to the authority figures? I got to feeling so mean and so miserable I most wished I was dead. I fidgeted up and down the raft, abusing myself to myself, and Jim was fidgeting up and down past me. We neither of us could keep still. Every time he danced around and says, "Dah's Cairo!" it went through me like a shot, and I thought if it WAS Cairo I reckoned I would die of miserableness. Jim talked out loud all the time while I was talking to myself. He was saying how the first thing he would do when he got to a free State he would go to saving up money and never spend a single cent, and when he got enough he would buy his wife, which was owned on a farm close to where Miss Watson lived; and then they would both work to buy the two children, and if their master wouldn't sell them, they'd get an Ab'litionist to go and steal them. It most froze me to hear such talk. He wouldn't ever dared to talk such talk in his life before. Just see what a difference it made in him the minute he judged he was about free. It was according to the old saying, "Give a nigger an inch and he'll take an ell." Thinks I, this is what comes of my not thinking. Here was this nigger, which I had as good as helped to run away, coming right out flat-footed and saying he would steal his children -- children that belonged to a man I didn't even know; a man that hadn't ever done me no harm. I was sorry to hear Jim say that, it was such a lowering of him. My conscience got to stirring me up hotter than ever, until at last I says to it, "Let up on me -- it ain't too late yet -- I'll paddle ashore at the first light and tell." I felt easy and happy and light as a feather right off. All my troubles was gone. I went to looking out sharp for a light, and sort of singing to myself. By and by one showed. Jim sings out: "We's safe, Huck, we's safe! Jump up and crack yo' heels! Dat's de good ole Cairo at las', I jis knows it!" I says: "I'll take the canoe and go and see, Jim. It mightn't be, you know." He jumped and got the canoe ready, and put his old coat in the bottom for me to set on, and give me the paddle; and as I shoved off, he says: "Pooty soon I'll be a-shout'n' for joy, en I'll say, it's all on accounts o' Huck; I's a free man, en I couldn't ever ben free ef it hadn' ben for Huck; Huck done it. Jim won't ever forgit you, Huck; you's de bes' fren' Jim's ever had; en you's de ONLY fren' ole Jim's got now." I was paddling off, all in a sweat to tell on him; but when he says this, it seemed to kind of take the tuck all out of me. I went along slow then, and I warn't right down certain whether I was glad I started or whether I warn't. When I was fifty yards off, Jim says: "Dah you goes, de ole true Huck; de on'y white genlman dat ever kep' his promise to ole Jim." Well, I just felt sick. But I says, I GOT to do it -- I can't get OUT of it. Right then along comes a skiff with two men in it with guns, and they stopped and I stopped. One of them says: "What's that yonder?" "A piece of a raft," I says. "Do you belong on it?" "Yes, sir." "Any men on it?" "Only one, sir." "Well, there's five niggers run off to-night up yonder, above the head of the bend. Is your man white or black?" I didn't answer up prompt. I tried to, but the words wouldn't come. I tried for a second or two to brace up and out with it, but I warn't man enough -- hadn't the spunk of a rabbit. I see I was weakening; so I just give up trying, and up and says: "He's white." "I reckon we'll go and see for ourselves." "I wish you would," says I, "because it's pap that's there, and maybe you'd help me tow the raft ashore where the light is. He's sick -- and so is mam and Mary Ann." "Oh, the devil! we're in a hurry, boy. But I s'pose we've got to. Come, buckle to your paddle, and let's get along." I buckled to my paddle and they laid to their oars. When we had made a stroke or two, I says: "Pap'll be mighty much obleeged to you, I can tell you. Everybody goes away when I want them to help me tow the raft ashore, and I can't do it by myself." "Well, that's infernal mean. Odd, too. Say, boy, what's the matter with your father?" "It's the -- a -- the -- well, it ain't anything much." They stopped pulling. It warn't but a mighty little ways to the raft now. One says: "Boy, that's a lie. What IS the matter with your pap? Answer up square now, and it'll be the better for you." "I will, sir, I will, honest -- but don't leave us, please. It's the -- the -- Gentlemen, if you'll only pull ahead, and let me heave you the headline, you won't have to come a-near the raft -- please do." "Set her back, John, set her back!" says one. They backed water. "Keep away, boy -- keep to looard. Confound it, I just expect the wind has blowed it to us. Your pap's got the small-pox, and you know it precious well. Why didn't you come out and say so? Do you want to spread it all over?" "Well," says I, a-blubbering, "I've told everybody before, and they just went away and left us." "Poor devil, there's something in that. We are right down sorry for you, but we -- well, hang it, we don't want the small-pox, you see. Look here, I'll tell you what to do. Don't you try to land by yourself, or you'll smash everything to pieces. You float along down about twenty miles, and you'll come to a town on the left-hand side of the river. It will be long after sun-up then, and when you ask for help you tell them your folks are all down with chills and fever. Don't be a fool again, and let people guess what is the matter. Now we're trying to do you a kindness; so you just put twenty miles between us, that's a good boy. It wouldn't do any good to land yonder where the light is -- it's only a wood-yard. Say, I reckon your father's poor, and I'm bound to say he's in pretty hard luck. Here, I'll put a twentydollar gold piece on this board, and you get it when it floats by. I feel mighty mean to leave you; but my kingdom! it won't do to fool with small-pox, don't you see?" "Hold on, Parker," says the other man, "here's a twenty to put on the board for me. Good-bye, boy; you do as Mr. Parker told you, and you'll be all right." "That's so, my boy -- good-bye, good-bye. If you see any runaway niggers you get help and nab them, and you can make some money by it." "Good-bye, sir," says I; "I won't let no runaway niggers get by me if I can help it." They went off and I got aboard the raft, feeling bad and low, because I knowed very well I had done wrong, and I see it warn't no use for me to try to learn to do right; a body that don't get STARTED right when he's little ain't got no show -- when the pinch comes there ain't nothing to back him up and keep him to his work, and so he gets beat. Then I thought a minute, and says to myself, hold on; s'pose you'd a done right and give Jim up, would you felt better than what you do now? No, says I, I'd feel bad -- I'd feel just the same way I do now. Well, then, says I, what's the use you learning to do right when it's troublesome to do right and ain't no trouble to do wrong, and the wages is just the same? I was stuck. I couldn't answer that. So I reckoned I wouldn't bother no more about it, but after this always do whichever come handiest at the time. I went into the wigwam; Jim warn't there. I looked all around; he warn't anywhere. I says: "Jim!" "Here I is, Huck. Is dey out o' sight yit? Don't talk loud." He was in the river under the stern oar, with just his nose out. I told him they were out of sight, so he come aboard. He says: "I was a-listenin' to all de talk, en I slips into de river en was gwyne to shove for sho' if dey come aboard. Den I was gwyne to swim to de raf' agin when dey was gone. But lawsy, how you did fool 'em, Huck! Dat WUZ de smartes' dodge! I tell you, chile, I'spec it save' ole Jim -- ole Jim ain't going to forgit you for dat, honey." Then we talked about the money. It was a pretty good raise -- twenty dollars apiece. Jim said we could take deck passage on a steamboat now, and the money would last us as far as we wanted to go in the free States. He said twenty mile more warn't far for the raft to go, but he wished we was already there. Hamlet spews out nihilistic conceits in 4.2. and 4.3., and continues to indulge in gallows humor in 5.1. until he wakes up to a new perspective toward afterlife while meditating on Yorick's skull. Since he pretty much moped around in suicidal thoughts, his awakening in 4.4 and 5.1 is so swift and surprising. Now Hamlet is ready to think and act like a king, even though he turns out to be a king we could have had but did not. At this point, the vulgarity, puns, and gallows humor are reassigned to the two grave diggers and one of them, the First Clown, seems to serve as the conventional fool who speaks out to the king (or prince). First Clown argues that Adam was the first grave digger and grave digging is a noble profession because Adam had (a coat of) arms. Second Clown contends it only to receive an answer that Adam dug with his arms. Here "arms" serves as a pun. These menial workers further undermine the arbitrary division of class by observing that a gallows maker builds the most durable monument in human history. It is not much different than saying all humans are common criminals and crooks. Hamlet's misanthropic rants seem to echo through the grave diggers' mouths. No more wading through self-hatred and nihilism, Hamlet banters with the grave digger and plays on the word, "lie." At the beginning, they both use "lie" to mean "stay," but soon its meaning changes and now both start to use it in term of "being laid in the grave." Since both are alive, neither can claim the grave as his and each man starts to accuse the other of lying. This pun introduces a comic relief to the play and also alerts the viewer's attention to the owner of the grave--Ophelia. What do you call ten alternately unstressed and stressed syllables?

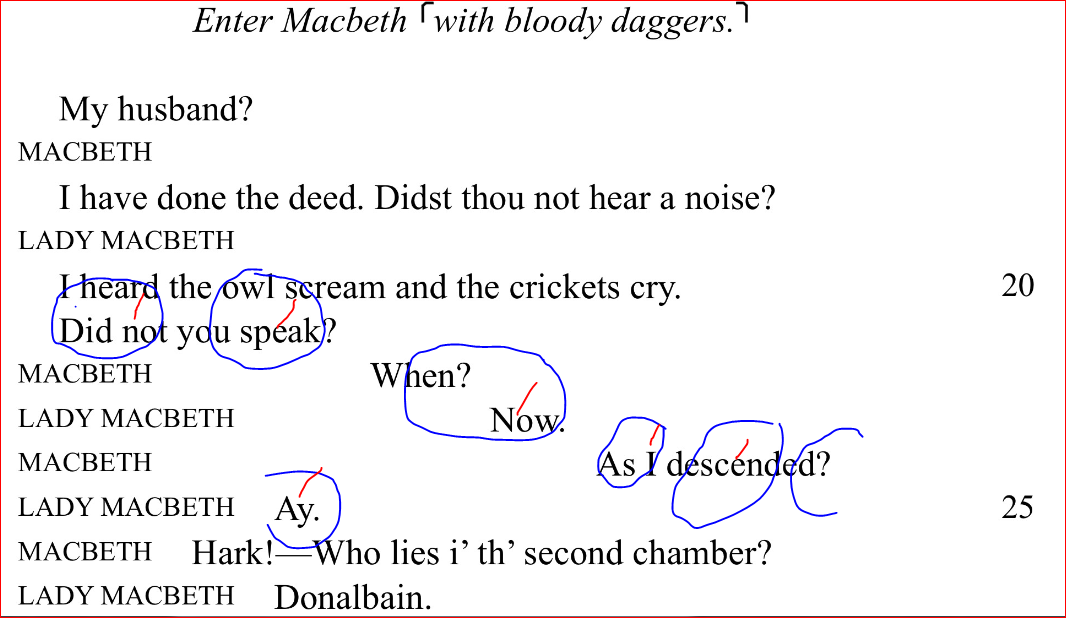

What do you call when the answer of the earlier question comes with "blank" rhyme (meaning without any rhyme)? Ha, too easy? Am I boring you? Or are you "board"? How's that for a pun? Now, try to explain why and how Macbeth and Lady Macbeth share one iambic pentameter and illustrate its dramatic effect. This frantic dialogue takes place right after the usurper Macbeth killed the unsuspecting king Duncan. Example 1: OPHELIA He hath, my lord, of late made many tenders* Of his affection to me. LORD POLONIUS Affection! pooh! you speak like a green girl, Unsifted in such perilous circumstance. Do you believe his tenders,** as you call them? OPHELIA I do not know, my lord, what I should think. LORD POLONIUS Marry, I'll teach you: think yourself a baby; That you have ta'en these tenders*** for true pay, Which are not sterling. Tender**** yourself more dearly; Or--not to crack the wind of the poor phrase, Running it thus--you'll tender***** me a fool. (Hamlet 1. 3. 99-109) * = tokens (possibly connoting guestures and gifts that convey tender feelings) ** = a formal offer or contract (as a marriage proposal) *** = something, esp money, used as an official medium of payment (which means it is not real money) **** = (verb) to offer something officially or formally (Polonius demands Ophelia to play hard to get.) ***** = (verb) to bring something (like a bastard) In addition, "green" in line 3 also means "tender." But, for once, Shakespeare checked himself from "out-punning" himself. Example 2: This is what Roxanne told me. A: Why did the football coach shake the vending machine? B: Because he wanted his quarter back! Example 3: "I see" said the blind man as he picked up his hammer and saw. The mute man picked up his wheel and spoke. The deaf man moved his cattle and herd. Example 4: I have a sin of fear, that when I have spun My last thread, I shall perish on the shore; Bug swear by Thy self, that at my death Thy Son Shall shine as he shines now, and heretofore; And, having done that, Thou has done; I fear no more. Above is a stanza from John Donne's "A Hymn to God the Father." Which word is used as a pun? |

|